|

| |

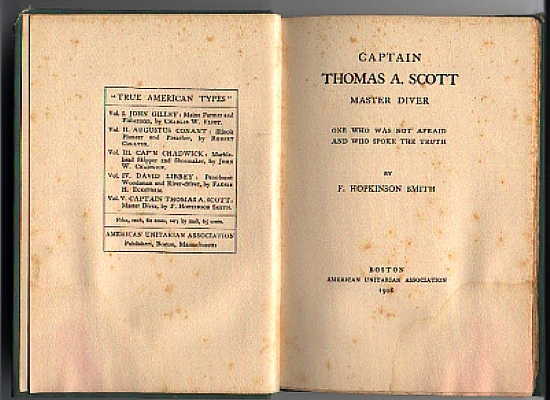

Francis

Hopkinson Smith’s 1908 book,

Captain Thomas A. Scott, Master Diver

Those

of you familiar with the lighthouse history of the United States, and particularly that of

the Long Island, NY area, know the story of the Race Rock lighthouse (You may see the Race

Rock lighthouse on various cruises conducted by the Long Island Chapter). This lighthouse

was among the most difficult of US lighthouses to build, due to its location in dangerous,

often unpredictable waters. It took seven years, several lives, and over $278,000 before

the light was first lit January 1, 1879. Race Rock’s builder, Francis Hopkinson

Smith, would go on to build the Ponce Inlet, Florida lighthouse, the base for the Statue

of Liberty, and other important works, but the ordeal of building the lighthouse upon Race

Rock would remain a large part of his life and his legacy. It was also a growing and

learning experience for him, as you will read in his own words below.

USCG Photo

This

book, a scant 76 pages long, was published by the American Unitarian Association in 1908

as part of their "True American Types" series. It is a tribute to Smith’s

foreman on the Race Rock project, Captain Thomas A. Scott. Captain Scott, as you will

read, was an uncommon man.

Many

thanks are owed to Diane Mancini for transcribing this book and for the many other

projects upon which she imparts her time and effort on the behalf of Long Island's

lighthouses.

Keep

in mind that Captain Thomas A. Scott, Master Diver was written in 1908. The

wording may seem unusual. Take your time. Download the page if need be and read it at your

convenience.

Ten

years prior to this book, Mr. Smith had written a fictional novel, Caleb West, Master

Diver, that was based upon his experiences with Captain Scott. We are currently

seeking a copy of this book.

If

you would like more information on Francis Hopkinson Smith, including a photo of him,

visit the Ponce Inlet lighthouse's excellent web site at: http://www.ponceinlet.org/ and click on

"History."

Enjoy.

*******************************************************

CAPTAIN SCOTT

Some sixty years ago—sixty-two, to be exact—there

sailed out of a harbor on the Chesapeake, near the town of Snow Hill, Maryland, a craft

carrying eight cords of wood—all on deck. She

was what was known as a "bay pungy," drawing but four feet of water, with a mast

forward and a boom swinging loose. Aft of the stump of a bowsprit was a fo'castle the size

of a dry goods box, in which slept the captain and crew.

The captain was Tommy Scott, a lad of fifteen,—strong, well-built, and

springy, with a look in his face of one who was not afraid, and who spoke the truth; the

crew was a Negro boy of twelve. These two supplied the neighboring towns with wood in

exchange for oysters and clams.

Some years later a straight, clear-eyed young fellow, with a chest of

iron—arms like cant hooks and thighs lashed with whip-cord and steel, shipped as

common sailor aboard the schooner John Willetts,—Captain Wever, Master. He was seven years older than when he commanded

the pungy, but the look on his face was still the same,—the look of a man who was not

afraid and who spoke the truth.

A leaf torn from the log of the Willetts—yellow stained and frayed at the

corners—a fragment hidden in an old trunk in the garret all these

years—furnishes a further record. From

this fragment it appears that a certain Thomas Scott was hired at fifteen dollars a month,

paid at intervals, as follows:

To cash at Port

Richmond……………….$2.00

To cash at New York…………………….1.00

To cash for shirt………………………..…1.50

To cash for trunk off Barnegat………….…2.00

Cash a dollar gold piece…………………..1.00

At the bottom were the words, 'All settled with T. Scott up to May 1st,

1852," and then the signature, "T.A. Scott."

Three years later (1855 now), another vessel loomed into view; this was the

schooner Thomas Nelson, Capt. Thomas A. Scott master and part-owner, loaded to the

scuppers with a cargo of staves bound for Barbadoes.

She carried but one passenger,—a slender Maryland girl with a wedding ring on

her finger which Captain himself had placed there three weeks before. The voyage took eighteen days, the sea being

smooth and the wind kindly—so kindly that the slender girl sometimes held the tiller. On the voyage back a gale from the northwest

swept the deck and split the foresail into ribbons. On

the tenth day the navigator and half the crew were taken down with fever, the navigator

dying as he reached port. Again the slender

girl held the tiller, standing beside the man who was not afraid,—this time with her

heart in her mouth: the Atlantic was an

unknown sea to her husband, but the wife and all he had in the world was aboard. Forty-eight hours the two stood on deck taking

turns at the pumps and tiller. On the

twenty-fifth day they sighted the Capes and the next morning dropped anchor in the

Roanoke. Many a storm have these two ridden

out together since that blind rush from the Barbadoes—storms of poverty, of death, of

sorrow—many a bright morning too, and welcoming harbor, have gladdened their eyes,

but there were always four hands on the tiller, two big and strong and two warm and

helping.

The children began to come now. The

schooner was sold and the Captain and his wife moved to Coytesville, N. J., where he

opened a general store. Two years later a

burning steamer sank near Fort Lee. The

Captain was asked to make a survey of the wreck, with the result that the store was

abandoned and a contract entered into between himself and the owners to bring the cargo to

the surface. This experience fitted him for

more important work along similar lines, and in 1869 he entered the employ of a sub-marine

company in New York, and was at once placed in charge of the wrecked steamer Scotland,

sunk in six fathoms of water off Sandy Hook, its site marked for many years by the U. S.

Government with the Scotland Lightship. The

steamer was an iron vessel, lay immediately in the channel and was a menace to navigation. The government paid a lump sum for its complete

removal and a percentage of the value of any cargo saved.

Up to the time Captain Scott was put in charge of this work, all attempts at

breaking the iron hulk had failed; explosives of to-day were unknown then; the battery was

in use, but a water-proof cartridge of high power was lacking. Captain Scott crawled over every foot of the

vessel in his diving dress, made up his mind instantly what to do, bought thirty new wine

casks holding sixty gallons each, filled them with powder, sunk and placed each cask

himself—some under her lower deck, others back of her boilers—two in the

forecastle, five behind her engines—wherever the force would tell, connected the

thirty giant bombs by rubber-coated copper wire, twisted the strands into one rope, placed

his battery in a rowboat, fell back some hundred yards and made the connection. There was an upheaval, a column of water straight

in the air, and the Scotland was split like a melon dashed on the sidewalk.

The fight for a clear channel being won, the work of salvage was begun. This occupied 585 working hours, Scott breaking

the record at that time by remaining seven hours and forty-eight minutes under water. The Company's share of the property saved amounted

to $110,000; Scott's pay and percentage to $11,000.

The following year (1870) he laid the under-water foundation for the first dock

built by the Dock Department of New York, the plan being a novel one, and his own.

Between 1871 and 1878 he was in charge, at my request, of the submarine work of the

Race Rock Lighthouse off New London Harbor, to which city he moved his plant and family,

and where they still reside.

Not much of a record, the foregoing—unless you knew the man were familiar with

the difficulties overcome. Hundreds of men in

similar walks of life have done as much, you might say many have done more; I admit it,

but few with so little book education. For

there had been no time during all these years for study; he had had practically no

schooling—only what his mother had taught him and what he could thumb from the

primers of the day—just a plain, American sailor-man—born of industrious, honest

people. His only capital, his courage, his

clear head, his willingness to tackle any job that came his way, and his mastery of

details.

My own acquaintance with him begins now,—one of the greatest blessings that

ever came into my life. This is easily

understood when my own unfitness for a task of the magnitude I had contracted to do is

considered. I was young, inexperienced, with

little money and with practically no plant for a work of the kind. The problem was the building of a lighthouse

exposed to the full rake of the Atlantic, situated eight miles from a harbor, two miles

from any shore, my first work of any magnitude, and in a "race" that ran six

miles an hour. The success of work of this

kind does not always depend on the skill of the engineer, but upon the nerve, pluck and

loyalty of the men who handle the material. These

men are difficult to obtain, for there are no regular working gangs from which to choose

them, there not being enough lighthouses built in any one year on our coasts to educate

and retain them. Moreover, every structure

presents a different problem in itself. Besides

experience in any branch such as diving, handling and erecting derricks is really less

important than the willingness to get wet and stay wet, hours at a time; to endanger one's

life almost daily without caring or knowing the risk; to go hungry when shut off from

supplies by rough weather, during which no landing can be made; to sleep in a water cask

for three days, if you will, lashed to the derricks, because every other movable

thing,—shanty and all,—has been swept away by a southeaster (and this was one of

our experiences). To do this cheerfully, patiently and continuously, year after year,

battling with the sea as an enemy, only looking forward to victory, is what crowns any

submarine work with success.

More difficult still is the finding of a man to lead and command such men.

One morning, in answer to my advertisement, a forceful, straightforward

man,—strong as a bull, clear-eyed, honest looking, competent and fearless, walked

into my office, a stranger, and thirty minutes later walked out again as foreman of

construction. He was about forty-two years of

age at the time, in the prime of his manhood and at the beginning of an experience now so

widely known. References usually considered

necessary in a first interview, and generally confirmed by subsequent inquiries or written

recommendations, did not enter into the negotiations between us. No man or child could look Captain Thomas A. Scott

in the face without instantly believing in him, and no act of his in after life would

shake that belief.

The reader must forgive the use of the personal pronoun in this part of the

Captain's life. I cannot tell it in any other

way and do him justice. This will be better

appreciated when it is remembered that during the seven years the Lighthouse was building,

we slept side by side in the same shanty, ate the same food and were often wet by the

smash of the same sea, and that during that time and for years thereafter, he was the

brains and force of all subsequent work contracted for in my office. Our friendship began gradually, step by step,

increasing in intensity as I watched him develop, noted his instantaneous command of

resources, his indomitable courage, knowing no fear, and his marvelous control over his

men. The sentiment deepened into

love,—the love a younger brother has for an older one, whom he looks up to and

depends upon as one difficulty after another, insurmountable to me, arose, and it became

permanent and life-long when his first great calamity overtook him—the blowing up of

his working boat, the Wallace, she proving a total wreck with heavy loss in killed and

wounded, and a heavy money loss to him of some $10,000.

The hands that could wrench a sea-jammed rock from its bed in thirty feet of water

were those of a woman now as he sat night after night in the improvised hospital we had

fitted up for the men's comfort, or stood by their graves with uncovered head.

Nor can this story be properly and truthfully told without a slight description of

the work his heroism and brains brought to completion.

The problem presented was the throwing overboard of thousands of tons of stone from

sloops, to form an artificial island upon which, when leveled to low water, there was to

be built a granite cone some sixty feet in diameter, and on this was to be placed the

dwelling house, topped by the lantern and lens.

This turtle island,—it was in the form of an ellipse,—was to be leveled

so smooth that the first course of masonry could be laid true. This was exceedingly difficult for the rocks

over this area weighed from three to seven tons, and were, of course, jagged, with their

points projecting sometimes several feet above the requisite level of mean low water, and

so covered with sea-slime and kelp as to make a slippery foothold. The current of the race, too, was swift,—so

much so that, should the men pull away from the island in small boats far enough to escape

the falling fragments of a blast to break these projections, they could not regain the

island again except in slack water. As a

protection against these fragments Captain Scott made trap doors of heavy oak plank

spliced together three or four feet square. The

men crouched up to their necks in water between the rocks before the blasts were fired,

and pulled these skids, or trap doors, over their heads.

Owing to Scott's watchfulness no skulls were cracked nor bones broken, and a

general thanksgiving took place in consequence.

At this stage of the work an

important discovery was made; in fact we had been making it ever since work began. Many of the loose rocks forming the artificial

island and which, in obedience to the Government's plan, had been thrown into the sea to

find their own bottom, were found to have altered their position. Soundings showed that the depth of water outside

the edge of the island, instead of being but twelve feet, as shown on the plan, was really

thirty feet. We were, therefore, building

the island on a pyramid, and not on a level surface.

These facts, of course, were known and thoroughly discussed by the

Government, and were as fully known to us. But

the department had decided to try the experiment of their not settling, rather than incur

the additional expense of leveling the whole shoal. The

impossibility of placing a granite cone weighing thousands of tons on such a foundation

now became apparent. The Government was

notified, and after some weeks of investigation, we were asked for a modified plan which

would utilize, as far as possible, the work already completed and paid for.

I recall now the days and

nights Captain Scott spent over this new problem and the number of models made and

abandoned by us as new difficulties and obstacles presented themselves. At last a plan, upon which the lighthouse was

finally built, was submitted to the board and approved. It was as follows:—

To chain and drag from the

center of the turtle's back by means of heavy derricks erected in a square on four points

of the island, all the three to five ton rock that had been dumped in, to replace these

rocks outside the circle of the proposed excavation, piling them up as a breakwater until

we had reached the original bottom and had uncovered the original Race Rock, a huge

boulder weighing some twenty tons, and then to fill this water space with concrete in the

form of a great disk up to the level of low water. Upon

this concrete disk, in reality one solid stone—the shape of a huge cheese—was to

be built the granite cone.

I recall, too, the months

of labor devoted to the chaining and dragging from its bed these submerged rocks, jammed

together as they were by succeeding winter's storms,—the work becoming more and more

difficult as the water deepened. Problems

like these are outside a manual; the time must come when a human body and a pair of human

hands, backed by courage and brains, must take sea after sea upon his back when working

above water, or while breathing through an inch hose when grappling them below the wave

break. No money can pay for such

labor;—nothing but loyalty to the work and his associates.

With the water space

cleared, the iron bands to circle the concrete were sunk and laid flat on the sandy

bottom, filled with concrete mixed in a soft state, packed into buckets with drop bottoms

and thus lowered to the divers below. This

was continued until four successive circles of filled iron bands, one on top of the

other,—a process occupying months—were laid and the disk struck smooth. The first base stone of the lighthouse,—a

mill-stone sixty feet in diameter and three feet thick, hard as an obelisk, and like it of

one solid stone,—was now complete.

No other problem confronted

us. The succeeding years of work were like

those always attending work of this class; there were storms, of course, with high surf,

so that the Rock could not be reached and there were set backs of one kind or another,

such as loss of shanties, platforms and every movable fixture. But the Captain's work was over, and one of the

lasting monuments of his skill and loyalty complete in all its details.

A digression here is

permissible—one that is illuminating. It

is but a few years back since this same old sea-dog—he was gray by this time, with a

bald spot on the back of his head and a trifle larger around the middle—boarded his

tug in East London harbor—he owned half a dozen of them then—took the younger

brother with him and pointed the tug's nose for the Race Rock light, finished twenty-five

years before.

"Good many holes out

there," the sea-dog said, as he plunged her nose head-foremost into the recurrent

waves surging in from Montauk, "and it git worse before it gits better."

As we neared the isolated

pile of masonry, a spot in the waste of waters that all these years had withstood the

attacks of the merciless sea, and still holds its light aloft—the figure of a man

slid down the iron ladder of the cone and ran to the end of the wharf. Then came a voice.

"Anything the matter?

Anybody sick?"

It was something out of the

ordinary for a New London tug to head for the Rock in the teeth of a southeaster.

"No,—just come

out to see if we could land," the Captain cried.

"Gosh!—how you

skeered me,—thought some of the folks was tuk bad."

Then another man dropped

down the ladder and springing to the boat's davits, began lowering a lifeboat.

"What d'yer think,

sir, shall we try it?" asked the Captain.

"Can we land?" I

asked dubiously.

"Land!—of

course," he replied with positive emphasis. "It

won't make no difference to me" (he was seventy-four then),—"but there

won't be a dry rag on you."

I picked up the glass and

looked over the joints of the masonry and followed the lines of the wharf and the angle of

the cone. They were still as true as when

Captain Tom had laid them with his own hands.

"Never mind, Captain,"

I said—"I guess you needn't bother."

What a difference

twenty-five years makes in some of us!

And it was not only in the

building of the light that his indomitable courage showed itself. The human side of the man—the woman side of

him, the side in which his tender nature showed itself—was even more lovable. Lovable is the word. You admire some men, you respect and fear others. Scott you loved.

What I am about to relate

is not fiction. I stood by and saw it

all,—it is true, word for word. There

are half a dozen men yet alive who held their breath, as I did, in fear. They have never forgotten what they saw,—and

never will.

"Hung on like a

terrier to a rat!" one old salt told me last winter in speaking of the event. "Seemed to shake 'er too, same's if he had

his teeth in 'er. Gosh!—but I was

skeered till I saw him come up 'an get his wind after that big sea hit him! Beat all what Captain Tom would do in them

days!"

It all occurred years

before; when the old salt now bent and grizzled was as hale and hearty as Captain Scott

himself.

We were at the time, the

old salt included, watching the movements of a sloop loaded with stone for the

Light,—the property of an old man and his wife who could ill afford its loss. Owing to the bad seamanship of her captain, a man

by the name of Baxter, the sloop had slipped her moorings from a safety buoy anchored

within a hundred yards of the Rock, had been sucked in by the eddy of the Race, and with

sail up was plunging bow on toward the lighthouse foundation. The error meant the sinking of the sloop and

perhaps the drowning of some of her crew. It

meant too hopeless poverty for the old man and his wife.

The weather had puzzled

some of us since sunrise; little lumpy clouds showed near the horizon line and sailing

above these was a dirt spot of vapor, while aloft glowed some prismatic sun-dogs,

shimmering like opals. Etched against the

distance, with a tether line fastened to the safety buoy, lay Baxter's sloop; her sails

furled, her boom swinging loose and ready, the smoke from her smoke-pipe thrust up out of

the forward hatch.

Below us on the concrete

platform rested our big air-pump, and beside it stood Captain Scott. He was in his diving dress, and at the moment was

adjusting the breast-plates of lead weighing twenty-five pounds each, to his chest and

back. His leaden shoes were already on his

feet. With the exception of his copper

helmet, the signal line around his wrist and the life-line about his waist he was ready to

go below.

This meant that pretty soon

he would don his helmet, and with a last word to his tender, would tuck his chin whisker

inside the opening, wait until the face plate was screwed on, and then with a nod behind

the glass, denoting that the air was coming all right, would step down his rude ladder

into the sea: to his place among the crabs

and the sea-weed.

Suddenly my ears became

conscious of a conversation carried on in a low tone around the corner of the shanty.

"Old Moon-face

(Baxter) 'Il have to git up and git in a minute," said a derrick-man to a

shoveler—born sailors these—"there'll be a helluver a time 'round here

'fore night."

"Well, there ain't no

wind."

"Ain't no

wind,—ain't there! See that bobble

waltzing in?" Seaward ran a ragged line

of silver, edging the horizon towards Montauk.

"Does look soapy,

don't it?" answered the shoveler. "Wonder

if the Cap'n sees it."

The Captain had seen

it—fifteen minutes ahead of anybody else—had been watching it to the exclusion

of any other object. That was why he hadn't

screwed on his face-plate. He knew the

sea—knew every move of the merciless, cunning beast.

The game here would be to lift the sloop on the back of a smooth under-roller and

with mighty lunge hurl it like a battering ram against the shore rocks, shattering its

timbers into kindling wood.

The Captain called to one

of his men—another shoveler.

"Billy, go down to the

edge of the stone pile and holler to the sloop to cast off and make for home. And say—" this to his pump

tender—"unhook this breast-plate; there won't be no divin' to-day. I've been mistrustin' the wind would haul ever

since I got up this mornin'."

The shoveler sprang from

the platform and began clambering over the slippery, slimy rocks like a crab, his red

shirt marked with the white X of his suspenders in relief against the blue water. When he reached the outermost edge of the stone

pile, where the ten-ton blocks lay, he made a megaphone of his fingers and repeated the

Captain's orders to the sloop.

Baxter listened with his

hands cupped to his ears.

"Who says so?"

came back the reply.

"Cap'n Scott."

"What fur?"

"Goin' to

blow—don't ye see it?"

Baxter stepped gingerly

along the sloop's rail; when he reached the foot of the bowsprit this answer came over the

water:

"Let her blow! This sloop's chartered to deliver this stone. We've got steam up and the stuff's going over the

side: git your divers ready. I ain't shovin' no baby carriage and don't you

forgit it. I'm comin' on! Cast off that buoy-line, you—" this to

one of his men.

Captain Scott continued

stripping off his leaden breast-plate. He

had heard his order repeated and knew that it had been given correctly,—and the

subsequent proceedings did not interest him. If

Baxter had anything to say in answer it was of no moment to him. His word was law on the Ledge; first, because the

men daily trusted their lives to his guidance, and second, because they all loved him with

a love hard for a landsman to understand, especially to-day, when the boss and the gang

never, by any possibility, pull together.

"Baxter says he's

comin' on, sir," said the shoveler when he reached the Captain's side, the grin on

his sunburnt face widening until its two ends hooked over his ears. The shoveler had heard nothing so funny for weeks.

"Comin' on!"

"That's what he

hollered. Wants you to git ready to take his

stuff, sir."

I was out of the shanty

now. I came in two jumps. With that squall whirling in from the eastward and

the tide making flood, any man who would leave the protection of the spar-buoy for the

purpose of unloading was fit for a lunatic asylum.

The Captain had

straightened up and was screening his eyes with his hand when I reached his side, his gaze

riveted on the sloop, which had now hauled in her tether line, and was now drifting clear

of the buoy. He was still incredulous.

"No,—he ain't

comin'. Baxter's all right,—he'll port

his helm in a minute,—but he'd better send up his jib—" and he swept his

eye around,—"and that quick, too."

At that instant the sloop

wavered and lurched heavily. The outer edge

of the inn-suck had caught her bow.

Minds work quickly in times

of great danger,—minds like Captain Scott's. In

a flash he had taken in the fast approaching roller, frothcapped by the sudden squall; the

surging vessel and the scared face of Baxter who, having now realized his mistake, was

clutching wildly at the tiller and shouting orders to his men, none of which could be

carried out. The Captain knew what would

happen—what had happened before, and what would happen again with fools like

Baxter—now—in a minute—before he could reach the edge of the stone pile,

hampered as he was in a rubber suit that bound his arms and tied his great legs together. And he understood the sea's game, and that the

only way to outwit it would be to use the beast's own tactics. When it gathered itself for the thrust and started

in to hurl the doomed vessel the full length of its mighty arms, the sloop's safety lay in

widening the space. A cushion of backwater

would then receive the sloop's forefoot in place of the snarling teeth of the low

crunching rocks.

He had kicked off both

leaden-soled shoes now and was shouting out directions to Baxter, who was slowly and

surely being sucked into the swirl:

"Up with your jib!

No,—No!—let that mainsail alone! UP! Do ye want to git her on the stone pile

you—Port your helm! PORT!! GOD!—LOOK AT HIM!!"

Captain Scott had slid from

the platform now and was flopping his great body over the slimy, slippery rocks like a

seal, falling into water holes every other step, crawling out on his belly, rolling from

one slanting stone to another, shouting to his men every time he had the breath:—

"Man that yawl and run

a line as quick as God'll let ye, out to the buoy! Do

ye hear! Pull that fall off the drum of the

h'ister and git the end of a line on it! She'll

be on top of us in a minute, and the mast out of her!

QUICK!!"

The shoveler sprang for a

coil of rope. The others threw themselves

after him, while half a dozen men working around the small eddy in the lea of the

diminutive island caught up the oars to man the yawl.

All this time the sloop,

under the up-lift of the first big Montauk roller—the skirmish line of the

attack—surged bow on to destruction. Baxter,

although shaking with fear, had sense enough left to keep her nose pointed to the stone

pile. The mast might come out of her, but

that was better than being gashed amidships and sunk in thirty fathoms of water.

The Captain, his rubber

suit glistening like a tumbling porpoise, his hair matted to his head, had now reached the

outermost rock opposite the doomed craft, and stood near enough to catch every expression

that crossed Baxter's face, who, as white as chalk, was holding the tiller with all his

strength, cap off, his blowsy hair flying in the increasing gale, his mouth tight

shut—no orders now would have done any good. Go

ashore she must and would, and nothing could help her.

It would be every man for himself then: no

help would come,—no help could come. Captain

Scott and his men would run for shelter as soon as the blow fell and leave them to their

fate. Pea-nut men like Baxter are built to

think that way.

All these

minutes—seconds really—the Captain stood bending forward, watching where the

sloop would strike, his hands out-stretched in the attitude of a ball player awaiting a

ball. If her nose should hit on the sharp,

square edges of one of the ten-ton blocks, God help her!

She would split wide open, like a gourd.

If by any chance her fore-foot should be thrust into one of the many gaps

between the enrockment blocks—spaces from two to three feet wide—and her bow

timbers thus take the shock, there was a living chance to save her.

A cry from Baxter, who had

dropped the tiller and was scrambling over the stone-covered deck to the bowsprit, now

reached the Captain's ears, but he never altered his position. What he was to do must be done surely. Baxter didn't count—wasn't in the back of

head; there were plenty of willing hands to pick Baxter and his men out of the suds.

Then a thing happened,

which, if I had not seen it, I would never have believed possible. The water cushion of the out-suck helped—so

did the huge roller which in its blind rage had under-estimated the distance between its

lift and the wide-open jaws of the rock—as a maddened bull often under-estimates the

length of its thrust, its horns falling short of the matador.

Whatever the cause, Captain

Scott saw his chance, sprung to the outermost rock, and bracing his great snubbing posts

of legs against its edge, reversed his body, caught the wavering sloop on his broad

shoulders, close under her bow-sprit chains, and pushed with all his might.

Now began a struggle

between the strength of the man and the lunge of the sea.

With every succeeding onslaught, and before the savage roller could fully life the

staggering craft to hurl her to destruction, Captain Tom, with the help of the out-suck,

would shove her back from the waiting rocks. This

was repeated again and again,—the men in the rescuing yawl meanwhile bending every

muscle to carry out the Captain's commands. Sometimes

his head was free enough to shout his orders, and sometimes both man and bow were

smothered in suds.

"Keep that fall

clear!" would come the order—"Stand ready to catch the yawl! Shut

that—" here a souse would stop his breath.

"Shut that furnace door! Do

ye want the steam out of the b'iler—" etc., etc.

That the slightest misstep

on the slimy rocks on which his feet were braced meant sending him under the sloop's bow

where he would be caught between her "fore-foot" and the rocks and ground into

pulp concerned him as little as did the fact that Baxter and his men had crawled along the

bowsprit over his head and dropped to the island without wetting their shoes, or that his

diving suit was full of water and he soaked to the skin.

Little things like these made no more difference to him than they would have done

to a Newfoundland dog saving a child. His

thoughts were on other things—on the rescuing yawl speeding towards the spar buoy, on

the stout hands and knowing ones who were pulling for all they were worth to that anchor

of safety, on two of his own men who, seeing Baxter's cowardly desertion, had sprung like

cats at the bowsprit of the sloop in one of her dives, and were then on the stern ready to

pay out a line to the yawl. No,—he'd

hold on "till hell froze over."

A hawser now ripped

suddenly from out the crest of a roller. The

two cats, despite the increasing gale, had succeeded in paying out a stern line to the men

in the yawl; who in turn had slipped it through the snatch block fastened in the spar

buoy, and had the connected it with the line they had brought with them from the island,

its far end being around the drum of our hoister.

A shrill cry now came from

one of the crew in the yawl alongside the spar buoy, followed instantly by the clear,

ringing order—"GO AHEAD!"

A burst of feathery steam

plumed skyward, and then the slow chuggity-chug of the shore drum cogs rose in the air. The stern lines straightened until it was as rigid

as a bar of iron—sagged for an instant under the slump of the staggering sloop,

straightened, and then slowly, foot by foot, the sloop, held by the stern line, crept back

to safety.

And this to save a friend

and his old wife from loss and, perhaps, poverty!

This love for his fellow

men and willingness to risk his life for their safety was not confined to his experience

on the Rock. He never referred to any of

these deeds thereafter;—never believed really that he had done anything out of the

ordinary. I myself had been with him for two

years before I learned of the particular act of heroism which I am now about to

relate—and only then from one of his men—an act which was the talk of the

country for days, and the subject of many of the illustrations of the time. I give it as it was told me, and word for word as

I have given it before. I do so the more

willingly and without excuse for its repetition here because it not only illustrates the

courageous but the tender, human side of the man. I

give it gladly, because the reading and rereading of such deeds helps to keep alive in the

hearts of our people that reverence for heroism which of late seems to be on the wane

among us. Our so-called up-to-date literature

is responsible for some of it; the absorption of our people in the material things of life

for much of it. Our heroes of to-day are

often the targets of the morrow. The thrill

that sent the blood of our young men rushing through their veins when the oft told story

of Valley Forge, Bunker Hill, or Gettysburg was poured into their ears, is nothing to the

breathless interest with which many of them read the head lines of a newspaper that tell

of ruined homes, wrecked reputations, and the misery and suffering involved. Now and then, it is true, when some brave fireman

crawls along a burning ledge, or the gateman on a ferry-boat risks his life to save a

would-be suicide, with the result that some official pins a medal on his chest, the heroic

act wins a place, but the record rarely covers more than ten lines of the issue, and even

then with the most important facts left out.

Of this incident it can be

safely said that nothing has been left out. Best

of all—it has been confirmed in all its details by the hero himself, after a

corkscrewing on my part that lasted for hours.

But to the story:

One morning in January,

when the ice in the Hudson River ran unusually heavy, a Hoboken ferry-boat slowly crunched

her way through the floating floes, until the thickness of the pack choked her paddles in

mid-river. The weather had been bitterly cold

for weeks, and the keen northwest wind had blown the great fields of floating ice into a

hard pack along the New York Shore. It was an

early morning trip, and the decks were crowed with laboring men and the driveways choked

with teams; the women and the children standing inside the cabins, a solid mass up to the

swinging doors. While she was gathering

strength for a further effort an ocean tug sheered to avoid her, veered a point, and

crashed into her side, cutting her below the water-line in a great V-shaped gash. The next instant a shriek went up from hundreds

of throats. Women, with blanched faces,

caught terror-stricken children in their arms, while men, crazed with fear, scaled the

rails and upper decks to escape the plunging of the overthrown horses. A moment more, and the disabled boat careened from

the shock and fell over on her beam helpless. Into

the V-shaped gash the water poured a torrent. It

seemed but a question of minutes before she would lunge headlong below the ice.

Within two hundred yards of

both boats, and free of the heaviest ice, steamed the wrecking tug Reliance of the

Off-shore Wrecking Company, making her way cautiously up the New Jersey shore to coal at

Weehawken. On her deck forward, sighting the

heavy cakes, and calling out cautionary orders to the mate in the pilot-house, stood

Captain Scott. When the ocean tug reversed

her engines after the collision and backed clear of the shattered wheel-house of the

ferry-boat, he sprang forward, stooped down, ran his eye along the water-line, noted in a

flash every shattered plank, climbed into the pilot-house of his own boat, and before the

astonished pilot could catch his breath ran the nose of the Reliance along the rail of the

ferry-boat and dropped upon the latter's deck like a cat.

If he had fallen from a

passing cloud the effect could not have been more startling. Men crowed about him and caught his hands. Women sank on their knees and hugged their

children, and a sudden peace and stillness possessed every soul on board. Tearing a life-preserver from the man nearest him

and throwing it overboard, he backed the coward ahead of him through the swaying mob,

ordering the people to stand clear, and forcing the whole mass to the starboard side. The increased weight gradually righted the

stricken boat until she regained a nearly even keel.

With a threat to throw

overboard any man who stirred, he dropped into the engine-room, met the engineer halfway

up the ladder, compelled him to return, dragged the mattresses from the crew's bunks,

stripped off blankets, racks of clothes, overalls, cotton waste and rags of carpet,

cramming them into the great rent left by the tug's cutwater, until the space of each

broken plank was replaced, except one. Through

and over this space the water still combed, deluging the floors and swashing down between

the gratings into the hold below.

"Another

mattress," he cried, "quick! All gone?—A blanket

then—carpet—anything—five minutes more and she'll right herself. Quick for God's sake!"

It was useless. Everything,

even to the oil rags, had been used.

"Your coat, then. Think of the babies, man;—do you hear

them?"

Coats and vests were off in

an instant; the engineer on his knees bracing the shattered planking, Captain Scott

forcing the garments into the splintered openings.

It was useless. Little by little the water gained, bursting out

first below, then on one side, only to be recaulked, and only to rush in again.

Captain Scott stood a

moment as if undecided, ran his eye searchingly over the engine-room, saw that for his

needs it was empty, then deliberately tore down the top wall of caulking he had so

carefully built up, and, before the engineer could protest, had forced his own body into

the gap with his arm outside level with the drifting ice.

An hour later the disabled

ferry-boat, with every soul on board, was towed into the Hoboken slip.

When they lifted Captain

from the wreck he was unconscious and barely alive. The

water had frozen his blood, and the floating ice had torn the flesh from his protruding

arm from shoulder to wrist. When the color

began to creep back to his cheeks, he opened his eyes, and said to the doctor who was

winding the bandages:—

"Wuz any of them babies

hurt?"

A month passed before he

regained his strength, and another week before the arm had healed so that he could get his

coat on. Then he went back to his work on

board the Reliance.

In the meantime the

Wrecking Company had presented a bill to the ferry company for salvage, claiming that the

safety of the ferry-boat was due to one of the employees of the Wrecking Company. Payment had been refused, resulting in legal

proceedings, which had already begun. The

morning following this action Captain Scott was called into the president's office.

"Captain," said

the official, "we're going to have some trouble getting our pay for that ferry job. Here's an affidavit for you to swear to."

The Captain took the paper

to the window and read it through without a comment, then laid it back on the president's

desk, picked up his hat and moved to the door.

"Did you sign

it?"

"No; and I ain't

a-goin' to."

"Why?"

"'Cause I ain't so

durned mean as you be. Look at this arm. Do you think I'd got into that hell-hole if it

hadn't been for them women cryin' and the babies a-hollerin'? And you want 'em to pay for it? Damn ye! If

your head wasn't white I'd mash it."

Then he walked out, cursing

like a pirate; the next day he answered my advertisement and the following week took

charge of the work at Race Rock.

Another hour of

corkscrewing made him remember the log of the Reliance, locked up in that same old trunk

in the garret from which the log of the Willetts was taken after his death. When the old well-thumbed book was found, he

perched his glasses on his nose, and began turning the leaves with his rough thole-pin of

a finger, stopping at every page to remoisten it, and adding a running commentary of his

own over the long-forgotten records.

"Yes,—here it

is," he said at last. "Knowed I

hadn't forgot it. You can read it yourself;

my eyes ain't so good as they wuz."

It read as

follows:—

"January 30, 1870. Left Jersey City 7 a.m. Ice running heavy.

Captain Scott stopped leak in ferry-boat."

But to continue:

The ending of the work on

the Rock found him a little over fifty years of age but still strong, muscular and with an

experience in submarine work second to no man on our coast.

Soon the docks in front of his home on Pequot Avenue, New London, began to be

enlarged: sheds were built, new tugs bought

and equipped, dredging machines constructed and heavy scows, barges and lighters carrying

cargoes of two hundred tons or more, were equipped with the best modern machinery. He was ready now for any heavy work, no matter how

large the steamer, how dangerous her position, or how serious the problem of refloating

her. The telephone was within reach of his

bedside, and no matter what the hour or how hard a gale was blowing, he was out and aboard

his fastest tug, often with a quart of raw oil dashed into the furnace and everything wide

open. It will be just as well to follow some

of these experiences:—The steamer Columbia, for instance, wrecked off Gay

Head—this in 1884.

The wreck lay

three-quarters of a mile from the promontory and the sea broke violently over it. Around the wreck were the steamers Storm King,

Conkling, Vincent, Hunter and Hunt, the latter having on board Captain Townsend, the New

Bedford diver, who was there in the interests of the Boston Underwriters. Captain Baker, of the Baker Wrecking Company of

Boston, was also there, waiting more favorable conditions to go below. Captain Scott recognized Captain Baker as having

charge of the wreck, and the latter said after a cursory survey that in his opinion a

diver could not stay under water in such weather, and that he would not send a man down. The New London diver characteristically replied

that he would send no man down either, but he would go himself. It was then resolved that an attempt should be

made about 3 p.m. if possible. Captain Scott

kept by the wreck, noting the condition of the water closely and made up his mind that if

he waited, Captain Baker's return he would lose the best chance for going under. He therefore began his preparations at 1 p.m. and

shortly before 2 o'clock dropped over the starboard side and made a thorough examination. He found a hole three feet square forward about

twenty feet from the stem and several smaller holes forward and abaft; also a

perpendicular crack near the foremast, while on the bottom were fragments of jagged rock

evidently broken from the larger boulders on which the ship struck. After completing the survey of the starboard side

along the bottom, Captain Scott came up and made an attempt to examine the deck. He went under at the forward hatch where he found

the deck uninjured, but he had no time to do more when he was caught in the crest of an

immense breaker and hurled feet foremost into the air.

The heavy seas breaking over the vessel prevented any further work that day.

On Friday morning Captain

Scott went out to the wreck in the Alert, but found a stiff breeze blowing and the water

too rough to admit of resuming operations. The

Alert, however, picked up three cases of boots and shoes, a portion of the cargo of the

City of Columbus, near Wood's Holl.

On Saturday the wind blew

fresh from the northwest, but the sea was moderate, the weather clear, and Captain Scott

was able to remain two hours under water and to complete his survey. He went down well aft on the port side and

examined along the bottom; he found portions of the smokestack and machinery, lines, sails

and other wreckage strewed along the port quarter by the main rigging. There was no material injury to the hull aft of

the boilers near the bottom, but there were numerous cracks and several holes forward. Further towards the bow the extent of the damage

increased, the hull being cracked and pierced with holes innumerable. The diver then went ahead of the wreck forty or

fifty feet and found himself in a submarine channel or sluiceway, making it evident that

the vessel struck a considerable distance ahead of her present position, and kept dropping

back by the influence of gravitation and the action of the tide, leaving the imprint of

her keel on the sandy bottom.

And again on January 12,

1890, when the magnificent steamer City of Worcester went ashore on the rocks inside

Bartlett's Reef Lightship. Within an hour of

the receipt of the news of the disaster, Captain Scott was speeding to her assistance in

his tug T. A. Scott, Jr., and was soon alongside the big, helpless steamer. The officers reported that the Worcester was fast

on the rocks with the water pouring into her second, third and fourth compartments and her

fires out. Life preservers were distributed,

the boats made ready, passengers landed without a single accident; most of the

cargo—1,250 bales of cotton being part—was transferred to lighters. Twenty-four hours thereafter the endangered

steamer was hauled from the rocks, towed into New London harbor, and anchored within a

stone's throw of Captain Scott's residence.

This list could be

continued indefinitely. Hardly a day or night

was the crew idle, and is not now, for his sons and associates still carry on the

business. Sometimes a diversion in the

customary work of recovering sunken property would occur. It

was a locomotive on one occasion; she had attempted to cross a trestle and had toppled

over in thirty feet of water, bottomed by mud.

"Get her

up?—" rejoined Captain Scott,—"certainly;—where'll I put

her?"

"Back on the

rails," said the general manager, with a laugh at the impossibility of the task.

"All

right,—she'll be there in the mornin'—" and she was.

It was but the work of half

a day for Captain Scott to rig up a pair of sheer poles, drop beside her in his diving

dress, pass some heavy chains under the boiler and between her axles, hook a block into a

ring, take a turn on a hoisting engine aboard his wrecking tug, open a steam cylinder and

up she came. To lower her gently to the rails

and wash her clean of the mud with a nozzle attached to the hose of his steam pump was the

last service.

"There—" he

said when she was scrubbed clean—"now git a fire under her and pull her

out;—she's in my way."

These instances, as I have said,

can be multiplied indefinitely,—enough, however, has been told to show the

fundamental incentive of his character—his determination to do his work

right,—so right that no man need ever perfect it after him. His superb constitution helped, but his

indomitable will helped more.

He never drank nor smoked,

and he neither had time nor desire to play cards. He

would go for forty-eight hours in wet clothes and think nothing of sleeping in them. He absolutely did not know what fear was for

himself, yet he feared for his men. He would

never send a man where he would not go himself, yet he'd go where he wouldn't send the

men. He never swore except in times of

danger, and then the oaths that came from his deep chest meant something "I've got to

do it," he'd say to me. "They won't

listen if I don't." So he'd swear at

the men to get out of the way of danger, to keep out of this place or that, to let him go

down instead of one of them. The result was

that they obeyed him implicitly. If he said

"Don't go!" they didn't. If he said

"Go!" they went, though it might be into a boiling surf or apparent death. They trusted his judgment in the face of

everything; and they were never deceived. When

a piece of work involved an extra hazardous risk he would say, "No that ain't no

place for you. I'll go."

And the harder the job, and

the more hopeless it seemed, the more cheerily he rose to the emergency, taking full

command and invariably doing the critical part himself.

When mounting our system of derricks for Race Rock, the crucial cable was the

outboard stay for the fourth derrick mast. At

the end of the stay was a hook, and this hook had to be slipped into a ring which was made

fast to a great block of stone out in the surf. When

it came time to windlass the last mast into position and adjust this hook, of course

somebody had to go into the surf to do it. The

sea was rising fast under a southeast wind, which always kicks up trouble at Race Rock,

and it demanded a man of great strength. So,

of course, the Captain went himself. Up to

his waist in a boiling surf, buried under the incoming rollers, he hung on to that hook

like grim death, swearing between mouthfuls of salt water to the men on the rocks, and in

spite of every effort of wind and tide to thwart us, he got the hook into the ring and

completed the derrick system that made possible the building of the Race Rock Light.

In fact, just here lay his

unique value. Whenever a situation confronted

us—one that the engineers in their offices could not solve, a situation where

theories and precedent counted for nothing and the only solution lay in the workman

himself, the Captain was the man who rose to the emergency.

For he could in any situation unite his great strength and manual skill to his keen

wits and inventive genius. Engineering feats

that would have been given up as hopeless he made possible by combining his brain with his

muscle. He thought like lightening too. Time and again I have seen him rescue his men when

it didn't seem possible that they could be saved. And

the smallest job received just as much attention and disinterested devotion from him as

the largest; nothing was ever shirked.

During the later years of

his life when he grew too stout to be in daily active service (he weighed over three

hundred pounds a few months before he died) the pent-up energy of the man seemed to have

found its outlet in the help he gave others. His

charity was so extensive, and he was so much beloved by every one, that at his funeral

there were six hundred people gathered in and about the house. Until the very day of his death he was busy

distributing bounties, sending children to school, looking after poor families up and down

the coast. One of the New London papers

remarked that it was hard to see how New London was going to live without Captain Scott. Only three days before his death he ordered a ton

of coal sent to a woman who scrubbed the floors of his house, and nearly his last act was

to call up the coal dealer on the telephone and upbraid him for delivering a cheaper grade

than he ordered, demanding that he take it out of the bin and substitute the better.

On the night of February 17th,

1907, when he had reached his seventy-seven years, the end came in the fine new home he

had built next his old cottage. It had been a

short time before that he had taken that same slender hand in his—the one that had

helped hold the tiller on their wedding journey—and the two crossed the intervening

lawn together. All the sons and daughters and

grandchildren were awaiting them in the spacious hall and adjoining rooms.

When the two dear old

people entered the house Captain Scott turned to his wife and said in that vibrant voice

of his which all who loved him knew so well:

"This is all yours,

Mrs. Scott. I guess our troubles are all over

now," and he dropped into a chair and cried like a child.

Summing him up in the

thirty-seven years I knew and loved him, he has always been, and will always be, to those

who had his confidence, one of nature's noblemen.—Brave modest, capable and

tender-hearted. The record of his life,

imperfectly as I have given it, must be of value to his fellow countrymen. Nor can I think of any higher tribute to pay him

than to repeat the refrain with which these pages were opened:—

"One who was not afraid, and who spoke the truth!" |